|

People In A

Position To Know may seem like a stuck-up name for a record label, but

head honcho Mike Dixon is just about as down-to-Earth as it gets. A

fixture for denizens of the indie rock underground, Dixon's prolific label

has garnered admiration from vinyl nerds across the globe. PIAPTK's

minuscule pressings and personalized production values have led to a loyal

following, and with plenty of ideas for future projects -- about which

Dixon remains cautiously tight-lipped -- there appears to be no end in

sight.

When not moonlighting as PIAPTK's wizard behind the scenes, Dixon teaches

Entrepreneurship and Accounting to high school students in Olympia, WA.

Ironically, the business practices of his label frequently run contrary to

the values he preaches in class. "The purpose of any good business is to

make money, and I've long since abandoned that philosophy. I'll be totally

shocked if I ever come close to breaking even," he explains. PIAPTK is

instead a labor of love, a classic Olympian DIY label in the vein of K

Records. Surprisingly, this is rarely appreciated by Dixon's students.

"Despite Olympia's reputation as a teenage indie rock heaven, the majority

of high schoolers here aren't interested in indie rock. It's predominantly

a hardcore, metal, and hip-hop scene, as are most small towns, I guess. I

occasionally play 'my kind' of music in class while they are working, and

they aren't exactly thrilled."

Dixon's initiation into indie rock was remarkably serendipitous. Raised in

Wichita Falls, a small town in Texas, he was funneled into the scene via

eighties punk.

"When I was 12, I went to a garage sale at the house of a

girl I had a huge crush on. She was 18 and had no idea I existed and had

just left home for college. Her parents were selling all of her cassette

tapes for a nickel each. I bought them based on the covers, because I

figured she was so amazing, she HAD to have good taste. I bought The

Replacements' Don't Tell A Soul, Dead Milkmen, Big Lizard

in my Backyard, The Smiths' Strangeways Here We Come

(in a Meat is Murder case), a dubbed copy of Half Japanese's

Half Gentlemen, Not Beasts in a homemade cover (with really cute

handwriting), and Husker Du's Candy Apple Grey."

The result was Dixon's transformation into

something more than a passive music

fan. "Radio rock (that is played twice an hour), as well as angsty, angry,

bro-dude rock, and familiar throwback stuff that sounds just like

everything you've already heard is a lot easier to 'get into.' It takes a

certain personality to completely reject the stuff that corporate America

is ramming down your throat. People like you and I don't really think

about it, because we are surrounded by 'active music fans,' people who go

out and search for good music and crave things that are a little

challenging." Indeed, sometimes it's unclear what sends some people on the

trail to becoming active fans, and others towards passivity. Often it's

just a matter of being in the right place at the right time, like a cute

girl's garage sale.

A split release between Tender Forever and Angelo

Spencer

Released on clear, heart-shaped vinyl.

PIAPTK was founded after Dixon made the move to Olympia. The label's first

release was a clear, square-shaped eight-inch record by The Arizona Quints.

Only twenty-five copies were made, and they have long since disappeared.

But that's part of the charm of owning a PIAPTK release. There is that

warm, buttery feeling you get from owning something that you know only a

few other souls possess. And perhaps more importantly, small runs allow

Dixon to allot a wealth of attention to a relatively minuscule group of

products. This means each one is treated like a work of art. As Dixon

points out, packaging plays an interesting role in a world where music no

longer has any physical value. "Everybody knows that you can get almost

any album you want for free. You can download entire discographies with

one click." However, some people still crave something they can hold. "You

have to make the object worth having, cherishing and showing off to

fellow record nerds. The only way to do that is to make the packaging

interesting. What would you rather have: something that was obviously made

with love, by hand, or something that rolled off a printing press after a

run of Tylenol boxes?" Where does this inevitably lead? "I think packaging

has become, or at least soon will, be a person's only incentive to buy

music." This makes for an interesting situation. Because music can be

converted to code, and code can be freely transmitted anywhere, it is only

the bare materials of a record that hold any value. The sole aspect of a

music release worth paying for is the visual artwork in which it is

embedded. Could this be a reaction to the increasing scarcity of material

product? As music proliferates with limited reliance on natural resources,

its physical manifestations become a luxury. Because of this, the only way

to attract the consumer to a musical product is to gussy up the release

itself. You make the record something worth owning, maintaining a market

based on visual aesthetic alone -- much like demand for hardcover books

sustained itself in the advent of more affordable soft-covers. Hence,

novel packaging ideas are a large part of what attracts both bands and

listeners to PIAPTK's releases. Notable records have included a Poster

Children EP on clear, triangular vinyl, a clear "faux picture disc" donned

in a hand-knit sleeve, and a one-sided, 8.375 inch Casiotone for the

Painfully Alone record done in two batches on either tan or brown

marble vinyl. Curiously, Dixon himself isn't one for designing the

packaging himself. "I'm a pretty horrible graphic artist, so my main

contributions are combing garage sales for weird packaging items or

slaving over a screenprinting board in my bedroom. I generally steer the

bands into certain packaging concepts, and they design the artwork

themselves."

Karl Blau's "Ho! Western Lands/Wing Flap Mantra"

Released on clear, triangular, eight-inch vinyl.

Another decision that needs to be made involves the actual production of

the records. What enables Dixon to create small runs of records in the

25-50 copy range is the existence of a small, home-run company called King

Records Worldwide. Operated in rural New Zealand by Peter King, King

Worldwide produces small editions of records that are lathe-cut - meaning

they are transparent, polycarbonate discs molded on equipment that King

built himself. Adding to the intrigue, King allegedly communicates solely

by fax and phone, and has never made the leap to the internet. As a

result, he has amassed a significant cult following. One particular

fanatic, Dan Vallor, runs a website that attempts to catalogue the immense

history of lathe-cut record. The resulting list takes up several pages

worth of text and is organized alphabetically and by record size. In

addition to the encyclopedic lists of record details, his website includes

the most recent rates at which King provides his record-making services.

Naturally, these are all listed in New Zealand dollars; however, at latest

conversion, seven-inch records will run you about $2.89 each, while

triangular records go for $4.91 apiece. Add to this shipping ($25.42 for

20 7" records mailed to North America) and the costs quickly mount. As a

result, Dixon sells his PIAPTK lathes at a relatively high break-even

point, allowing him to give some copies to the band and keep some for

himself. His rationale is simple: "I have no need to make money on the

label, because I have a real job that pays me enough money to live on. I

just want to make my money back so that I can continue to make more

records without going into the hole any further than I need to." This also

helps separate the fans from the less devoted patrons; PIAPTK's latest

release, an eight-inch square cut from Denton blues-punk band New

Science Projects, will run you thirteen dollars.

Dixon's other option is to get his records 'professionally' done. Because

the costs per unit are lower for a large-scale pressing, he is able to

mark them up a little bit. This isn't a greedy attempt to squeeze a little

cash out of the enterprise, but instead a way of cushioning the loss

incurred by the releases that never sell out, or only do so after several

years. Recently, the financial conundrum posed by a garage full of unsold

records has led to a gravitation towards limited editions. "The more

limited they are, the quicker they sell and recoup and the quicker that

money can go into more records - for the obvious reason of there not being

as many to sell, but also because the collector nerds like myself feel

like it is a little more urgent to buy early." There are also hidden costs

that must be considered - such as screen printing supplies and the

assorted paraphernalia that go into packaging each release -- as well as

the intangibles, namely the tireless hours Dixon spends putting the record

sleeves together. In fact, time is a major concern -- but not one that he

complains about. Fortunately, Dixon is innately and unshakably industrious

-- the anti-slacker, if you will:

"I am a workaholic and am only really comfortable when I

have a schedule, goal, and deadline. I've never been able to handle

downtime well. I would say that I, quite literally, spend 75% of my free

time, at the very least, either answering emails, packing orders, or

dealing with the day to day stuff of running the label. But, I really

enjoy it, and I guess it's better than playing World of Warcraft for 18

hours a day like my roommate does."

Jad Fair with Daisy Cooper EP

Released on square, 10-inch vinyl.

The last big concept for PIAPTK was the "Trust Series," a subscription

club wherein each customer was mailed seven eight-inch EPs one at a time,

as they were released. The catch? You had to trust Dixon. The bands

involved in the project were kept top secret, each one only revealed once

the record arrived in the mail. This, of course, was a somewhat

paradoxical concept in a world where bands and artists have become

increasingly conceptualized as brand names as opposed to creative

entities. Adding to the charm of the series, only twenty-five copies of

each record were made (meaning only 25 customers could join the club), and

each record came with a silk-screened cover done by hand. Naturally,

production was carried out by Peter King's lathe-cut business. As Dixon

explains:

"The results were great, and

pretty much what I expected. I sold about half of them immediately (I have

a handful of people who are really great about supporting the label and

the artists), and then the other half slowly sold as I started putting out

new stuff and getting mentioned on various blogs and things. It was kind

of vanity project... 'Here, you are going to pay for these (relatively

expensive) records in advance and not even get to know who is on them.'

And I told everyone up front that they would probably have never heard of

the bands. So, I intentionally didn't give anyone a real tangible

incentive to buy it."

In describing the rationale behind the Trust Series' design, Dixon

provides some useful advice for any potential micro-label owners. The

pragmatic details of the series came about due to the tribulations

involved in realizing PIAPTK's first limited edition subscription club. "I

had a LOT of great bands that were really into the idea, but ended up

flaking out, or taking much longer than expected to get me their

tracks. It definitely taught me not to (pardon my cliches) 'count my

chickens before they hatched'." So, the Trust Series was constructed with

more foresight. "I waited until I had all of the recordings in hand, and

the first two records of the series ready to go before I sold any of the

subscriptions. But […] there is a pretty significant turnaround time

getting records from Peter. He's a one-man operation, and he has a pretty

sizable clientèle. And, in the end, they are totally worth the wait."

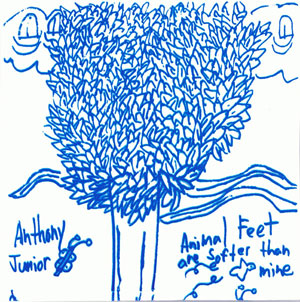

Anthony Junior's "Animal Feet are Softer than Mine"

The first release in the Trust Series.

The latest project for PIAPTK is a series of four-way split LPs featuring

"geographically centralized artists that are good friends." The first

edition focused on the Pacific Northwest, and collected tracks from Karl

Blau, Gift Machine, Graves, and Nick Ashley. If that wasn't enough, you

could select the particular record you wanted -- Dixon made 50 copies on

swampy green marble, 75 on purple, and 375 on grey marble. As of my

writing, only copies on purple and grey are still available. The genesis

of this project reflects the makeshift -- or, preferably, serendipitous -

manner in which PIAPTK's releases can sometimes come together:

"[The] idea kind of grew out of

what was going to be the second Limited Edition Subscription club. When

that whole thing turned out to be pretty impractical (and a little

overdone) I still had tracks from all these great artists. I noticed that

a lot of them (because I had let the bands choose who they wanted to do a

split with) tended to be close in proximity and bands that had

collaborated, toured together, etc. So basically, I just named/qualified

what was already happening and put a label on it. It was originally going

to be 7"s, but I personally prefer LPs to 7"s, so I put two split 7"s

together to make a four-way split."

For Dixon, all this work -- all the planning, all the coordinating, and

even all the hours spent stuffing liners into record sleeves -- is worth

it when he connects with like-minded record geeks. "Well, it's not a lot

of people, but there are a few people who buy the majority of my records.

There are definitely at least 3 or 4 that have been there from the

beginning and have every single one. And I also have new people every

release who buy 'the Complete PIAPTK' (one of each record) and then start

buying all of my new releases. You have no idea how much that means to

me." Like so many other subcultural phenomena, PIAPTK seems just as much

about social connection as it is about amassing shelves worth of limited

edition records. The joy of fostering a fan base of frequent flyers is not

about making money -- for Dixon, breaking even is often little more than a

pipe dream -- but instead about sharing in a ritual. And as physical

manifestations of music become increasingly obsolete, the sense of shared

identity that accompanies the ritual is strengthened. Perhaps in

celebration of this, Dixon recently put out a triangular record by Karl

Blau available free to anyone who has purchased eighteen or more PIAPTK

releases. Although cynics might call this a reward for obedience, Dixon

prefers to conceptualize it as a holiday gift to a small group of friends.

And I'm inclined to believe him.

-- Michael Tau

March 4, 2009

|